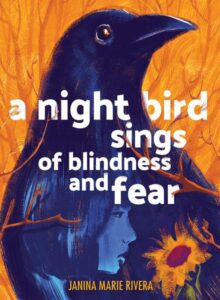

From the Book, A Night Bird Sings of Blindness and Fear

It’s one thing to eat chicken served fried on the table and another to see it lifeless and pale, sitting in a kitchen sink prior to cleaning. Naked, yes, that is how it feels. Feather-plucked chicken me, speechless in shame.

To say that I felt like an exposed raw chicken, as I lay on the cold medical table at the Singapore General Hospital, is an understatement. I caught the gaze of twelve pairs of eyes staring at me, as if calculating which limb or leg or wing would be best eaten first. My arms with all their bony joints? My ribs protruding from my skin? My skinny legs? I suddenly felt an urge to pull up my pink pajamas, but I held back. The nurse remarked, “She has dry skin.”

I was fourteen years old at that time, diagnosed with what is called an AVM, or an Arterio-Venous Malformation of the brain. While other girls my age fussed about the latest fashion trends or the hottest new boy band in town, there I was, chicken-like, my hair smelling like the antiseptic of the hospital. I was absent from the girlish gossip, teenage flirtation, and the mall lakwatsa so necessary in high school. My excuse? A vein had ruptured in my brain.

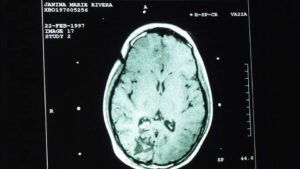

Actual X-Ray of Janina’s Brain with AVM

Actual X-Ray of Janina’s Brain with AVM

As my brain angiogram was about to start, I thought it would be one of those quick and painless little things. My doctors in the Philippines had done it to me before. They had put me to sleep under the dream-inducing cloud of general anesthesia. There in lala land, I wasn’t a lifeless chicken. No, I was General Jan, a soldier princess of everything beautiful and mountainous. I held a sword in one hand, fighting all sorts of dragons and lions and devils, while my other hand held a scepter with which I could command fairies, and miracles, and tiny, little crawling ladybugs. I could stop time, too. I would stretch a second by merely clapping my hands, then unfreeze the second with another clap.

When a nurse injected me near the groin, I felt my leg jerk up involuntarily in the air. Now was a good moment to freeze time!

I winced as my dry skin turned into dragon scales. “We’ll insert a tube in here,” she said, referring to a spot where an artery ran between my pelvis and my leg. “We will insert the tube so that the dye can pass through.” I felt the catheter enter my body. It was being pushed deep into the artery like a plastic snake. The next thing I knew, I felt the slight wiggling of the tube at the base of my neck.

Sample Catheters Used during Angiograms

Sample Catheters Used during Angiograms

I strained to look at the apparatus above me, hovering like some alien from outer space. It had big, white-painted metallic arms that were heavily jointed. It was the angiogram machine. It stood almost the complete height of the room. At the end of its arms were black discs, like flying saucers. On cue, they generated X-ray electromagnetic radiation to image my brain.

I thought I saw giant black eyes peering at me from the snake-like arms.

“You see me?” I asked the snake.

“Yes, I see you,” came the hiss.

“They’ll take pictures,” explained one doctor, bringing me back to reality. “They’re just like X-rays, but on a higher level than an ordinary X-ray or even an MRI.”

“Will it hurt?” I asked.

“It will,” said the doctor. “We have to do this because the angiogram will locate the exact area and depth of your AVM. We cannot do any kind of brain surgery unless we get the information from your angiogram.”

An Angiogram Machine

An Angiogram Machine

An AVM is considered a ticking time bomb of the brain, an abnormality that forms in a person while he is still an embryo (about 7 to 12 weeks old) inside his/her mother’s womb. It is a silent sleeper made up of veins and arteries that fused together wrongly because capillaries in the affected area did not grow properly. An AVM may give clues to its existence—a migraine here, a headache there, perhaps even a seizure or two. However, there are many times, like in my case, when it sits still and quiet, much like an unprovoked toad on a lily pad, suddenly jumping mercilessly at an unexpected moment.

August 11, 1996, was supposed to be an ordinary night. While the moon gave no clue to my AVM, it can be said that an invisible night bird, straight from the stories of my fairy tale books, rested its wings on me. It picked me up by its claws and carried me to a castle where a dragon was known to swoop from the sky and breathe fire on everything alive. All I felt of this evil bird’s presence was a soft coldness upon my ear.

Although I had my own bedroom, I usually slept in my parents’ room. Papa and Mama always gave an invitation for everyone to snuggle in the same room, our mattresses littered on the floor.

That fateful night, everyone, except my eldest brother, slept in my parents’ room. The air-conditioning unit was on, buzzing its lullaby. I dragged the mattress from my bed and lay right next to my mother. After closing my eyes, I soon fell into the lightest of sleeps.

“Are you okay?” Mama asked, as I tossed and turned. It was around 2 a.m. I couldn’t explain why I felt uncomfortable, as if the insides of my belly were coiling around each other. I shifted my body into various positions: I lay on my side, then on my back, then lay prostrate, then clutched at my pillow, then let go of my pillow.

I got up from the mattress. “I need to use the toilet, Mama.”

After relieving myself in the bathroom, I began to feel awful. I vomited violently into the toilet, and then again when I came back to the bedroom.

Mama was worried. “Did you eat anything bad?”

“I ate the take-home fried chicken, like you all did,” I said. “And I had a chocolate bar after.”

My stomach turned. I rushed back into the bathroom and vomited again. After that, I began retching non-stop. It came in strong rushes. When the food stopped coming out of my mouth, I started vomiting saliva instead.

My father was not at home that night since he was on night shift at the hotel where he worked as a manager. My mother called him on the phone, quickly telling him that I might have been food poisoned. I could only catch snippets of the conversation.

“We need to take Janina to the hospital.”

“Now?”

“Yes. I’ll call Baby.”

Tita Baby, or Mrs. Bautista, whom we fondly called “Ms. Bau,” was one of my teachers in high school. She lived a block away and drove a yellow station wagon. She had always been a jolly teacher. But that night, lines creased her face, and she pursed her lips as she and Miss Anguluan, one of my other teachers, helped Mama and me into her car.

We said hurried goodbyes to my four brothers. My youngest brother, Justin Emmanuel—who was turning two months old the next day—was fast asleep in his crib. My other brothers woke up and worriedly watched the car speed away.

I leaned on my Mama. In her hands was a tabo, which she used to catch my vomit as the car sped out of the village.

I clutched my head. What was this? Why did my head hurt? Wasn’t my stomach supposed to hurt since I was vomiting? I continued to retch, spilling putrid air and saliva into the tabo.

“How are you?” asked Mama.

“I’m seeing everything like shattered glass,” I managed to say.

Because no one had seen the invisible night bird alighting on my shoulder, no one thought that I was in a state of mortal distress.

Editor’s Note: The full story of Janina Marie Rivera’s bout with AVM can be found in the book, A Night Bird Sings of Blindness and Fear, published by OMF Literature.

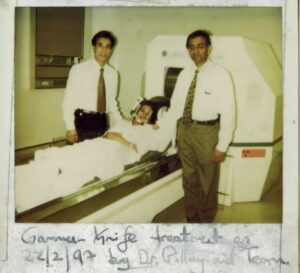

In Singapore, Undergoing Gamma Knife Stereotactic Radiosurgery

In Singapore, Undergoing Gamma Knife Stereotactic Radiosurgery

This excerpt was earlier published in One Voice Magazine’s website on Feb. 3, 2021.

Janina Marie Rivera is the author of the book, A Night Bird Sings of Blindness and Fear and has co-authored the devotional, Dawns, published by OMF Literature. She is a contributing poet in the books Joyful Light and Whitmanthology: on Loss and Grief by Various Authors. She is the Editor-in-Chief of One Voice Magazine.